Unpacking the Paradoxes of Sam Altman: The Complexities of an AI Evangelist

Balancing Innovation and Ethical Concerns: Inside the Mind of ChatGPT CEO Leading the Charge in AI Development and Responsible Implementation.

Sam Altman, the 37-year-old startup-minting guru at the forefront of the artificial intelligence boom, has long dreamed of a future in which computers could converse and learn like humans.

One of his clearest childhood memories is sitting up late in his bedroom in suburban St. Louis, playing with the Macintosh LC II he had gotten for his eighth birthday when he had the sudden realization: “Someday, the computer was going to learn to think,” he said.

In recent months, Mr. Altman has done more than anyone else to usher in this future—and commercialize it. OpenAI, the company he leads, in November released ChatGPT, the chatbot with an uncanny ability to produce humanlike writing that has become one of the most viral products in the history of technology. In the process, OpenAI went from a small nonprofit into a multibillion-dollar company, at near record speed, thanks in part to the launch of a for-profit arm that enabled it to raise $13 billion from Microsoft Corp., according to investor documents.

This success has come as part of a delicate balancing act. Mr. Altman said he fears what could happen if AI is rolled out into society recklessly. He co-founded OpenAI eight years ago as a research nonprofit, arguing that it’s uniquely dangerous to have profits be the main driver of developing powerful AI models.

He is so wary of profit as an incentive in AI development that he has taken no direct financial stake in the business he built, he said—an anomaly in Silicon Valley, where founders of successful startups typically get rich off their equity.

“Like most other people, I like watching scores go up,” when it comes to financial gains, he said. “And I just like not having that be any factor at all.” (The company said he earns a “modest” salary but declined to disclose how much.) Mr. Altman said he has a small stake in a venture fund that invested in OpenAI, but that it is “immaterial.”

Mr. Altman said he made “more money than I could ever need” early in his career when he made a fortune investing in young startups. He owns three homes, including a mansion in San Francisco’s Russian Hill neighborhood and a weekend home in Napa Valley, and employs a couple of dozen to manage them and his family office of investments and nonprofits.

During one of his last visits to his grandmother, who died last year, he bought her groceries and then admitted to his mother that he hadn’t been to a grocery store in four or five years, she said.

His goal, he said, is to forge a new world order in which machines free people to pursue more creative work. In his vision, universal basic income—the concept of a cash stipend for everyone, no strings attached—helps compensate for jobs replaced by AI. Mr. Altman even thinks that humanity will love AI so much that an advanced chatbot could represent “an extension of your will.”

In the long run, he said, he wants to set up a global governance structure that would oversee decisions about the future of AI and gradually reduce the power OpenAI’s executive team has over its technology.

Backers say his brand of social-minded capitalism makes him the ideal person to lead OpenAI. Others, including some who’ve worked for him, say he’s too commercially minded and immersed in Silicon Valley thinking to lead a technological revolution that is already reshaping business and social life.

The company signed a $10 billion deal with Microsoft in January that would allow the tech behemoth to own 49% of the company’s for-profit entity, investor documents show. The corporate partnership, along with Mr. Altman’s push to more aggressively commercialize its technology, have disillusioned key early leaders at OpenAI who felt the decisions violated an initial commitment to develop AI outside the influence of shareholders.

One of OpenAI’s critics has been Elon Musk, who co-founded the nonprofit in 2015 but parted ways in 2018 after a dispute over its control and direction. The Tesla Inc. CEO tweeted in February that OpenAI had been founded as an open-source nonprofit “to serve as a counterweight to Google, but now it has become a closed-source, maximum-profit company effectively controlled by Microsoft. Not what I intended at all.”

OpenAI was created as an open source (which is why I named it “Open” AI), a non-profit company to serve as a counterweight to Google, but now it has become a closed source, maximum-profit company effectively controlled by Microsoft.

Not what I intended at all. — Elon Musk (@elonmusk) February 17, 2023

Mr. Altman paused when asked about his co-founder’s critique. “I like Elon,” he finally responded. “I pay attention to what he has to say.”

In an open letter made public this week, Mr. Musk and other Silicon Valley luminaries, including Apple Inc. co-founder Steve Wozniak, called for a six-month pause for developing AI more advanced than GPT-4, the latest technology released by OpenAI in March, to stem a technological race that could spiral out of control.

Mr. Altman said he doesn’t necessarily need to be first to develop artificial general intelligence, a world long imagined by researchers and science-fiction writers where software isn’t just good at one specific task like generating text or images but can understand and learn as well or better than a human can. He instead said OpenAI’s ultimate mission is to build AGI, as it’s called, safely.

OpenAI has set profit caps for investors, with any returns beyond certain levels—from seven to 100 times what they put in, depending on how early they invested—flowing to the nonprofit parent, according to investor documents. OpenAI and Microsoft also created a joint safety board, which includes Mr. Altman and Microsoft Chief Technology Officer Kevin Scott, that has the power to roll back Microsoft and OpenAI product releases if they are deemed too dangerous.

The possibilities of AGI have led Mr. Altman to entertain the idea that some similar technology created our universe, according to billionaire venture capitalist Peter Thiel, a close friend of Mr. Altman’s and an early donor to the nonprofit. He has long been a proponent of the idea that humans and machines will one day merge.

ChatGPT’s release triggered a stream of competing AI announcements.

“They’ve raced to release press releases,” Mr. Altman said of his competitors. “Obviously, they’re behind now” Google announced it was testing its own chatbot, Bard, in February and opened access to the public in March.

In its founding charter, OpenAI pledged to abandon its research efforts if another project came close to building AGI before it did. The goal, the company said, was to avoid a race toward building dangerous AI systems fueled by competition and instead prioritize the safety of humanity.

OpenAI’s headquarters, in San Francisco’s Mission District, evoke an affluent New Age utopia more than a nonprofit trying to save the world. Stone fountains are nestled amid succulents and ferns in nearly all of the sun-soaked rooms.

Mr. Altman gushes about the winding, central staircase he conceived so that all 400 of the company’s employees would have a chance to pass each other daily—or at least on the Mondays through Wednesdays they are required to work in-person. The office includes a college-style cafeteria, a self-serve bar and a library modeled after a combination of his favorite bookstore in Paris and the Bender Room, a quiet study space on the top floor of Stanford University’s largest library.

Dressed in the typical tech CEO uniform of a gray hoodie, jeans and blindingly white sneakers, Mr. Altman described a much more modest upbringing.

Mr. Altman grew up in a suburb of St. Louis, the eldest of four children born to Connie Gibstine, a dermatologist, and Jerry Altman, who worked various jobs, including as a lawyer, and died five years ago. The senior Mr. Altman’s true vocation was running affordable housing nonprofits, his family said, and he spent years trying to revitalize St. Louis’s downtown.

Among the lessons his father taught him, Mr. Altman said, was that “you always help people—even if you don’t think you have time, you figure it out.”

Dr. Gibstine said her son was working the family’s VCR at age 2 and rebooking his own plane ticket home from camp at 13. By the time he was in third grade, he was helping teachers at his local public school troubleshoot computer problems, she said. In middle school, he transferred to the private John Burroughs School.

“Teachers liked him because he was really, really bright and a hard worker, but he was also super social,” said Andy Abbott, the head of school, who was a principal at the time. “He was funny and had a big personality.”

Mr. Altman went on to Stanford, where he did research at an AI lab. By sophomore year he had co-founded Loopt, a location-based social networking service. It became part of the first class of Y Combinator, a startup accelerator that went on to hatch companies like Airbnb Inc., Stripe Inc. and Dropbox Inc., and Mr. Altman left school.

Loopt never got traction, selling in 2012 for $43.4 million, or close to the amount investors including Sequoia Capital put in.

Mr. Altman then started a venture fund and made powerful allies, including Mr. Thiel and Paul Graham, who co-founded Y Combinator and eventually brought on Mr. Altman. There he helped build the company into a Silicon Valley power broker. He invested his own money in dozens of successful companies early on, including cloud software company Asana Inc. and message-board site Reddit Inc.

While running Y Combinator, Mr. Altman began to nurse a growing fear that large research labs like DeepMind, purchased by Google in 2014, were creating potentially dangerous AI technologies outside the public eye. Mr. Musk has voiced similar concerns about a dystopian world controlled by powerful AI machines.

Messrs. Altman and Musk decided it was time to start their own lab. Both were part of a group that pledged $1 billion to the nonprofit, OpenAI Inc.

Mr. Musk didn’t respond to requests for comment.

The nonprofit meandered in its early years, experimenting with projects like teaching robots how to perform tasks like solving Rubik’s Cubes. OpenAI laid off a chunk of its small staff in 2017.

OpenAI researchers soon concluded that the most promising path to achieve artificial general intelligence rested in large language models or computer programs that mimic the way humans read and write. Such models were trained on large volumes of text and required a massive amount of computing power that OpenAI wasn’t equipped to fund as a nonprofit, according to Mr. Altman.

“We didn’t have a visceral sense of just how expensive this project was going to be,” he said. “We still don’t.”

That year, Mr. Altman said he looked into options to raise more money for OpenAI, such as securing federal funding and launching a new cryptocurrency. “No one wanted to fund this in any way,” he said. “It was a really hard time.”

Tensions also grew with Mr. Musk, who became frustrated with the slow progress and pushed for more control over the organization, people familiar with the matter said.

OpenAI executives ended up reviving an unusual idea that had been floated earlier in the company’s history: creating a for-profit arm, OpenAI LP, that would report to the nonprofit parent.

Reid Hoffman, a LinkedIn co-founder who advised OpenAI at the time and later served on the board, said the idea was to attract investors eager to make money from the commercial release of some OpenAI technology, accelerating OpenAI’s progress.

“You want to be there first and you want to be setting the norms,” he said. “That’s part of the reason why speed is a moral and ethical thing here.”

The decision further alienated Mr. Musk, the people familiar with the matter said. He parted ways with OpenAI in February 2018.

Mr. Musk announced his departure in a company all-hands, former employees who attended the meeting said. Mr. Musk explained that he thought he had a better chance at creating artificial general intelligence through Tesla, where he had access to greater resources, they said.

A young researcher questioned whether Mr. Musk had thought through the safety implications, the former employees said. Mr. Musk grew visibly frustrated and called the intern a “jackass,” leaving employees stunned, they said. It was the last time many of them would see Mr. Musk in person.

Soon after, an OpenAI executive commissioned a “jackass” trophy for the young researcher, which was later presented to him on a pillow. “You’ve got to have a little fun,” Mr. Altman said. “This is the stuff that culture gets made out of.”

Mr. Musk’s departure marked a turning point. Later that year, OpenAI leaders told employees that Mr. Altman was set to lead the company. He formally became CEO and helped complete the creation of the for-profit subsidiary in early 2019.

OpenAI said that it received about $130 million in contributions from the initial $1 billion pledge, but that further donations were no longer needed after the for-profit’s creation. Mr. Musk has tweeted that he donated around $100 million to OpenAI.

In the meantime, Mr. Altman began hunting for investors. His break came at Allen & Co.’s annual conference in Sun Valley, Idaho in the summer of 2018, where he bumped into Satya Nadella, the Microsoft CEO, on a stairwell and pitched him on OpenAI. Mr. Nadella said he was intrigued. The conversations picked up that winter.

“I remember coming back to the team after and I was like, this is the only partner,” Mr. Altman said. “They get the safety stuff, they get artificial general intelligence. They have the capital, they have the ability to run the compute.”

Mr. Altman shared the contract with employees as it was being negotiated, hosting all-hands and office hours to allay concerns that the partnership contradicted OpenAI’s initial pledge to develop artificial intelligence outside the corporate world, the former employees said.

Some employees still saw the deal as a Faustian bargain.

OpenAI’s lead safety researcher, Dario Amodei, and his lieutenants feared the deal would allow Microsoft to sell products using powerful OpenAI technology before it was put through enough safety testing, former employees said. They felt that OpenAI’s technology was far from ready for a large release—let alone with one of the world’s largest software companies—worrying it could malfunction or be misused for harm in ways they couldn’t predict.

Mr. Amodei also worried the deal would tether OpenAI’s ship to just one company—Microsoft—making it more difficult for OpenAI to stay true to its founding charter’s commitment to assist another project if it got to AGI first, the former employees said.

Microsoft initially invested $1 billion in OpenAI. While the deal gave OpenAI its needed money, it came with a hitch: exclusivity. OpenAI agreed to only use Microsoft’s giant computer servers, via its Azure cloud service, to train its AI models, and to give the tech giant the sole right to license OpenAI’s technology for future products.

“You kind of have to jump off the cliff and hope you land,” Mr. Nadella said in a recent interview. “That’s kind of how platform shifts happen.”

“The deal completely undermines those tenets to which they secured nonprofit status,” said Gary Marcus, an emeritus professor of psychology and neural science at New York University who co-founded a machine-learning company.

Mr. Altman “has presided over a 180-degree pivot that seems to me to be only giving lip service to concern for humanity,” he said.

Mr. Altman disagreed. “The unusual thing about Microsoft as a partner is that it let us keep all the tenets that we think are important to our mission,” he said, including profit caps and the commitment to assist another project if it got to AGI first.

The cash turbocharged OpenAI’s progress, giving researchers access to the computing power needed to improve large language models, which were trained on billions of pages of publicly available text. OpenAI soon developed a more powerful language model called GPT-3 and then sold developers access to the technology in June 2020 through packaged lines of code known as application program interfaces, or APIs.

Mr. Altman and Mr. Amodei clashed again over the release of the API, former employees said. Mr. Amodei wanted a more limited and staged release of the product to help reduce publicity and allow the safety team to conduct more testing on a smaller group of users, former employees said.

Mr. Amodei left the company a few months later along with several others to found a rival AI lab called Anthropic. “They had a different opinion about how to best get to safe AGI than we did,” Mr. Altman said.

Anthropic has since received more than $300 million from Google this year and released its own AI chatbot called Claude in March, which is also available to developers through an API.

In a recent investment deck, Anthropic said it was “committed to large-scale commercialization” to achieve the creation of safe AGI, and that it “fully committed” to a commercial approach in September. The company was founded as an AI safety and research company and said at the time that it might look to create commercial value from its products.

In the three years after the initial deal, Microsoft invested a total of $3 billion in OpenAI, according to investor documents.

More than one million users signed up for ChatGPT within five days of its November release, a speed that surprised even Mr. Altman. It followed the company’s introduction of DALL-E 2, which can generate sophisticated images from text prompts.

The internet blew up with anecdotes about people using ChatGPT to create sonnets or plan toddler birthday parties.

By February, it had reached 100 million users, according to analysts at UBS, the fastest pace by a consumer app in history to reach that mark.

Mr. Altman’s close associates praise his ability to balance OpenAI’s priorities. No one better navigates between the “Scylla of misplaced idealism” and the “Charybdis of myopic ambition,” Mr. Thiel said.

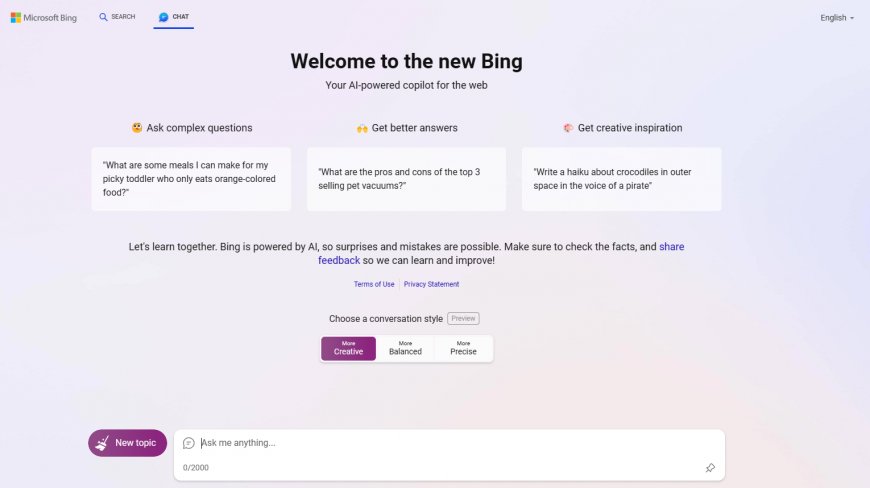

Mr. Altman said he delayed the release of the latest version of its model, GPT-4, from last year to March to run additional safety tests. Users had reported some disturbing experiences with the model, integrated into Bing, where the software hallucinated—meaning it made up answers to questions it didn’t know. It issued ominous warnings and made threats.

“The way to get it right is to have people engage with it, explore these systems, study them, to learn how to make them safe,” Mr. Altman said.

After Microsoft’s initial investment is paid back, it would capture 49% of OpenAI’s profits until the profit cap, up from 21% under prior arrangements, the documents show. OpenAI Inc., the nonprofit parent, would get the rest.

Mr. Altman’s other projects include Worldcoin, a company he co-founded that seeks to give cryptocurrency to every person on earth.

He has put almost all his liquid wealth in recent years in two companies. He has put $375 million into Helion Energy, which is seeking to create carbon-free energy from nuclear fusion and is close to creating “legitimate net-gain energy in a real demo,” Mr. Altman said.

He has also put $180 million into Retro, which aims to add 10 years to the human lifespan through “cellular reprogramming, plasma-inspired therapeutics and autophagy,” or the reuse of old and damaged cell parts, according to the company.

He noted how much easier these problems are, morally, than AI. “If you’re making nuclear fusion, it’s all upside. It’s just good,” he said. “If you’re making AI, it is potentially very good, potentially very terrible.”